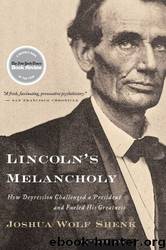

Lincoln's Melancholy: How Depression Challenged a President and Fueled His Greatness by Joshua Wolf Shenk

Author:Joshua Wolf Shenk [Shenk, Joshua Wolf]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: United States, Politics & Government, Nonfiction, Biography & Autobiography, 19th Century, Psychology, Mental Illness, Presidents & Heads of State

ISBN: 978-0547526898

Publisher: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

Published: 2005-07-01T04:00:00+00:00

Emancipation threw oil on the fire of Lincoln’s northern opposition, the antiwar Democrats, or Copperheads, who began to actively oppose a war that they argued, with increasing success, was really about freeing Negroes and enslaving whites. In January 1863, Lincoln said that he feared this “fire in the rear” even more than the military struggle. Indeed, the two fires began to burn together. While the war’s northern opponents seized on every piece of bad news—defeats in battle, high taxes, conscription—Confederate leaders saw that every blow they struck had a political as well as a military effect. In May, Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia bested a Union force twice its size at Chancellorsville. His confidence high, Lee then invaded southern Pennsylvania in early June, believing he could crush northern morale and perhaps secure diplomatic recognition from England and France.

Either way, Lee’s invasion was bound to be a turning point, and Lincoln hoped that it could bring the war to an end. These hopes were buoyed when, over the first three days of July, around the small crossroads town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, the Union army under General George Meade prevailed in a huge, ugly battle that left 50,000 dead, wounded, or missing. Lee lost 28,000 men, a third of his army, and limped back to the Potomac River, only to find the river swollen by rain and his pontoon bridges wrecked. He was trapped. Meanwhile, on July 4, General Ulysse S. Grant captured Vicksburg, the Confederate fortress that for more than two years had held the Mississippi River. Hearing this, Lincoln was in a rare good mood—“very happy,” wrote his secretary John Hay, “in the prospect of a brilliant success.”

His hopes were dashed, though, when Meade failed to pursue Lee. With three days to build a new bridge, the Confederates scampered safely back to Virginia. Robert Todd Lincoln, in a visit with his father, noted that he was “grieved silently but deeply about the escape of Lee.” Underscoring the troubles of war, on July 13 riots broke out in New York City, a culmination of months of unrest over a March draft law. The law made all men between the ages of twenty and forty-five eligible for military conscription, while exempting anyone who could pay $300. A combination of resentments—political, economic, racial—ignited groups of Irish immigrants, who sacked homes and lit buildings on fire. Blacks in particular felt their wrath. The Colored Orphan Asylum was burned to the ground. In four days of rioting about 120 people died. On July 14, Lincoln was, in his own words, “oppressed” and in “deep distress.” “My dear general,” he wrote to Meade, “I do not believe you appreciate the magnitude of the misfortune involved in Lee’s escape. He was within your easy grasp, and to have closed upon him would, in connection with our other late successes, have ended the war. As it is, the war will be prolonged indefinitely . . . I am distressed immeasurably because of it.” But the damage was already done.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

Cat's cradle by Kurt Vonnegut(15309)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(14468)

4 3 2 1: A Novel by Paul Auster(12356)

Underground: A Human History of the Worlds Beneath Our Feet by Will Hunt(12075)

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(12003)

Wiseguy by Nicholas Pileggi(5754)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(5414)

Perfect Rhythm by Jae(5386)

American History Stories, Volume III (Yesterday's Classics) by Pratt Mara L(5288)

Paper Towns by Green John(5165)

Pale Blue Dot by Carl Sagan(4986)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4941)

The Mayflower and the Pilgrims' New World by Nathaniel Philbrick(4475)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(4475)

Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI by David Grann(4427)

The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen(4372)

Too Much and Not the Mood by Durga Chew-Bose(4321)

The Borden Murders by Sarah Miller(4298)

Sticky Fingers by Joe Hagan(4177)